The Central Banks - Part 4

Why this matters: We’ve been digging into central banking’s messy roots -from the Land Bank of Massachusetts to Alexander Hamilton and the First Bank of the United States. Now we’re at Andrew Jackson, the guy who’d rather shoot a banker than shake his hand. This isn’t just a history lesson—it’s the story of who gets to control the money and what happens when they do. Last week, we cracked open the Mandrake Mechanism—how governments print cash to dodge hard choices. Here’s the flip side: what happens when a pissed-off populist torches the whole system instead? Jackson’s war on the Second Bank isn’t some dusty relic—it’s a brawl over power that echoes today, from Fed debates to crypto rants. Our current president keeps his portrait close for a reason. Stick with me - this one’s got teeth.

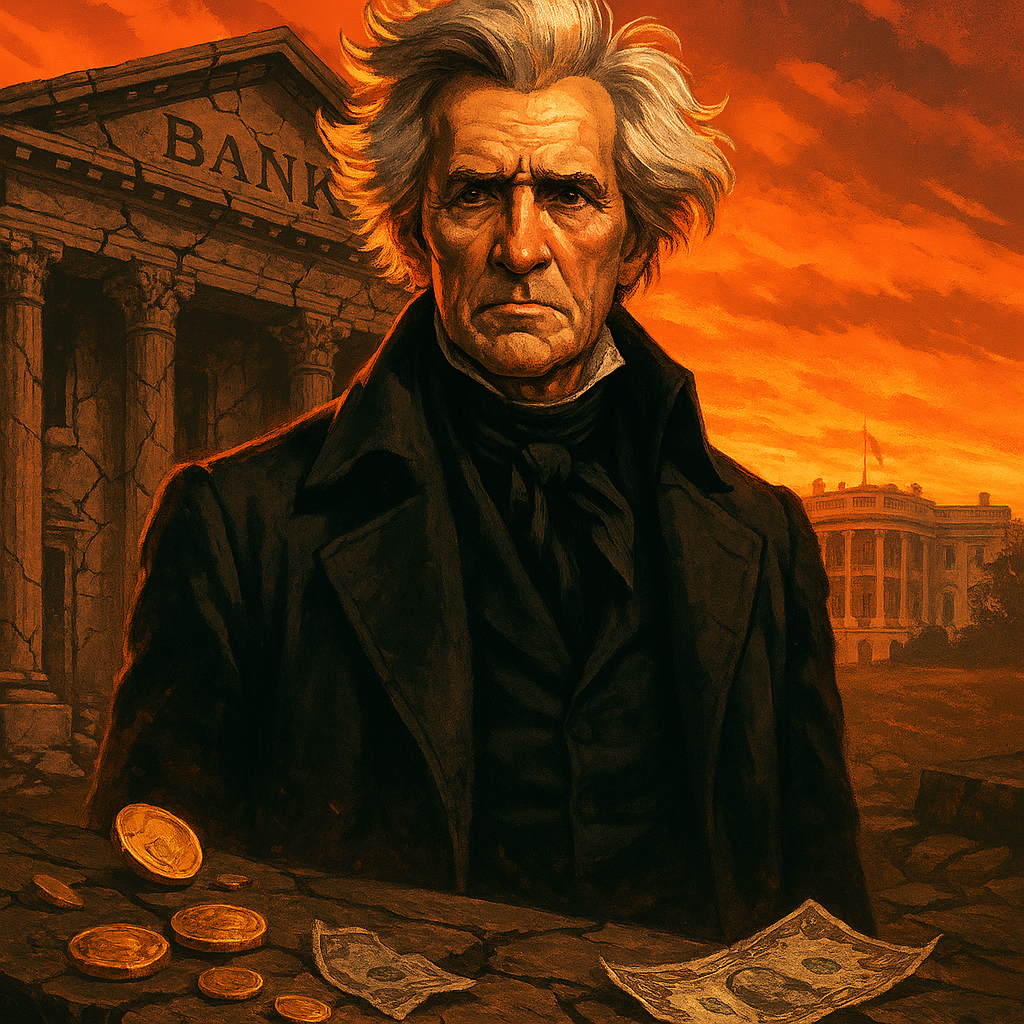

He walked with a bullet lodged permanently in his chest, spat contempt at entrenched power, and carved his name into the American psyche with the rage of a man who saw tyranny behind every gilded institution. Andrew Jackson was not a banker. He was a brawler, a duelist, a populist war hero who detested centralized financial control—and in 1833, he went to war with the most powerful financial institution in the United States: the Second Bank of the United States.

Every once in a while, history gifts us a fascinating, divisive, forceful personality like President Andrew Jackson. It’s also important to understand Jackson, as our current president has a great affinity for the man, and he has his portrait hanging in his office.

Jackson didn’t emerge from the salons of Philadelphia or the drawing rooms of New England. He roared out of the raw frontier - a man forged by war, death, and duels. Orphaned by fourteen, shaped by battlefields and borderlands, Jackson embodied a different kind of America: proud, defiant, and unconcerned with the polite restraints of the elite class.

By the time he reached the White House in 1829, Jackson had already become a legend. He was the Hero of New Orleans, a general who defeated the British with a ragtag militia and sheer will. But he was also a man consumed by a lifelong suspicion of power - especially the kind of invisible, unaccountable power wielded by financiers and their allies in government.

The Clash of the Titans

The Battle of the Second Bank of the United States involved two characters who were larger than life. On the side of the populist, agrarian republic (Jefferson’s position) was Andrew Jackson. On the other was Nicholas Biddle, Jackson’s primary nemesis and the leader of the Second Bank.

Nicholas Biddle was Jackson’s opposite in nearly every way—a patrician from Philadelphia, polished and precocious, fluent in Greek and Latin by age twelve, a graduate of Princeton at fifteen. He believed deeply in order, stability, and the civilizing power of institutions.

Where Jackson saw banks as engines of corruption, Biddle saw them as essential scaffolding for a growing nation. Under his stewardship, the Second Bank of the United States became one of the most powerful financial institutions in the world—stabilizing the currency, disciplining reckless state banks, and attracting European capital to American shores. Biddle viewed himself as a banker and a steward of national prosperity. And he fiercely believed that entrusting that stewardship to demagogues or mobs would spell financial ruin. In his eyes, Jackson was a dangerous barbarian who threatened to destroy the mechanisms that made American growth possible. To Jackson, Biddle was the aristocrat incarnate, symbolizing everything corrupt and unaccountable. Their collision would become one of the most consequential showdowns in American economic history.

The Founding of the Second Bank of the United States

The nation was in trouble in the aftermath of the War of 1812. As we’ve discussed before, wars are expensive. The War of 1812 was no different. Democracies, when faced with the choice to tax their citizens or borrow (to fund an unpopular war, much the less), will often choose to borrow or deflate the currency to fund it. Side note - important to note - the War of 1812 was a senseless and unnecessary war by most metrics, and the people of The United States knew that at the time.

So, the US Government borrowed heavily—mostly by issuing bonds at exorbitantly high interest rates—to pay for it. Remember that the United States was not a sure thing at the time, and picking a fight with Great Britain was tantamount to destruction. As a result, like anything in life, the price of the bonds needed to reflect the risk, so very high rates.

As discussed in The Mandrake Mechanism last week, there’s an easy solution for most governments today. They simply print money to pay the debt. The issue is that, after the war, there was no such centralized mechanism.

Let’s double-click on this point because it’s super important. The Constitution (Article I, Section 8) gave Congress the power to “coin money” and “regulate the value thereof.” Critically, it also did not give it the power to issue paper money (also known as “Bills of Credit”). In addition, Article I, Section 10 explicitly prohibited states from issuing their own currency or bills of credit. This left a strange gap: the federal government didn’t issue currency—and neither did the states.

So, who steps into the breach? Private and state-chartered banks were printing their own banknotes. These notes circulated as money, but their value varied wildly.

Thus, in the aftermath of the War of 1812, the government went on a borrowing binge and had no real way to “monetize” its debt. What the US had was absolute chaos.

With the charter of the First Bank having expired in 1811, the federal government had no central clearinghouse for debt, no coordinated banking infrastructure, and no control over the money supply. State banks had stepped into the void, but most were undercapitalized, barely regulated, and happily printing their own paper notes without the gold or silver to back them. The result was rampant inflation, a currency crisis, and an utter breakdown in public financial confidence.

In response, Congress created the Second Bank of the United States in 1816—a 20-year chartered institution designed to fix the mess. It was tasked with acting as the government’s fiscal agent, managing its debt payments, collecting taxes, and—perhaps most importantly—restoring order to the monetary system. It was capitalized with a then-massive $35 million. It had the power to open branches across the country, discipline reckless state banks by demanding specie payments, and issue a uniform national currency.

In theory, it would bring stability. In practice, it brought power. And that power would soon come under fire from a president who didn’t trust anyone—or anything—he couldn’t shoot.

The Veto Heard ‘Round the Country

By 1832, the Second Bank of the United States was only halfway through its 20-year charter. But Nicholas Biddle, ever the tactician, decided it was time to make a move. He pushed Congress to recharter the Bank early, thinking he could corner Jackson into a political checkmate. If Jackson vetoed the recharter, he’d look like an enemy of stability and prosperity in an election year. If he signed it, Biddle would secure the Bank’s future—and Jackson would eat crow.

But Biddle underestimated his opponent.

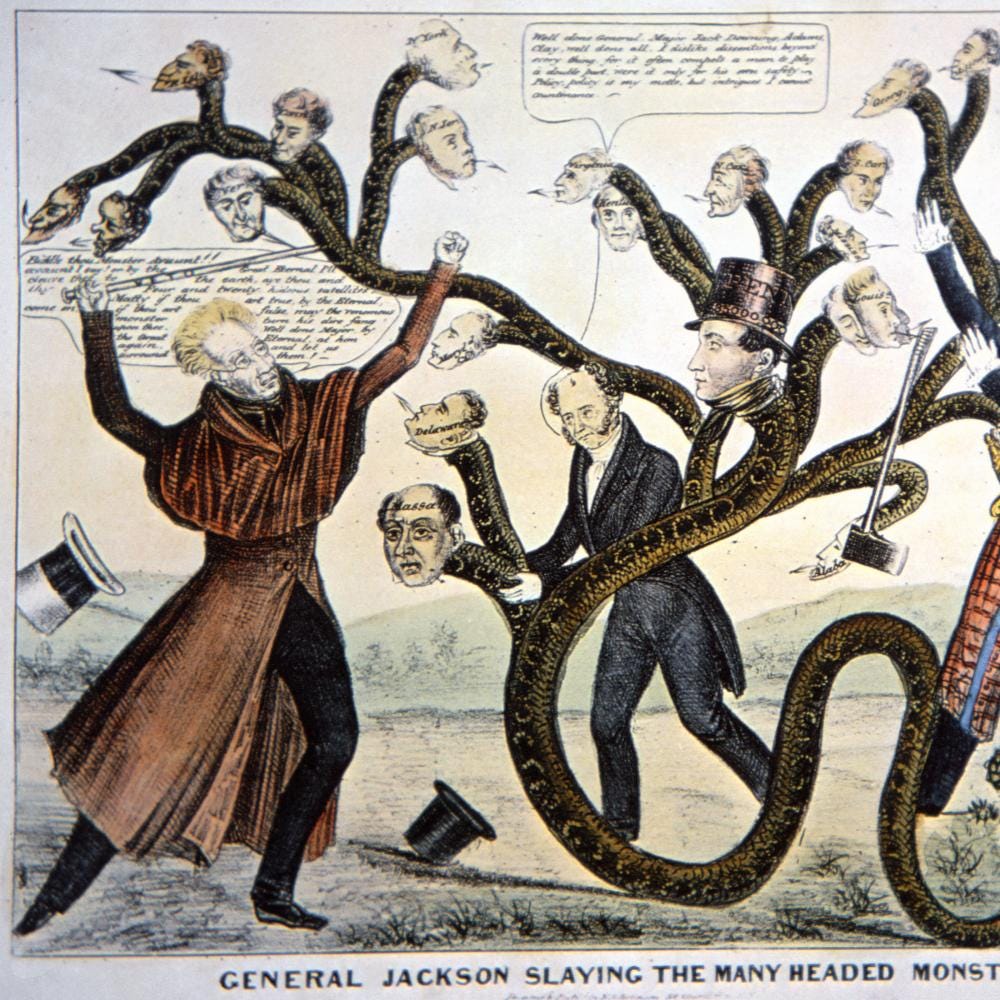

Jackson didn’t flinch. He vetoed the recharter with the fury of a man who believed he was facing down a financial Hydra—one that threatened to strangle American democracy in the cradle. His veto message wasn’t bureaucratic. It was thunderous. He accused the Bank of being a monopoly that favored the wealthy and well-connected at the expense of the common man. He framed it as a battle not over finance—but over freedom.

Here’s the tone he struck:

“It is to be regretted that the rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes… When the laws undertake to add to these natural and just advantages artificial distinctions… to make the rich richer and the potent more powerful, the humble members of society… have a right to complain of the injustice of their Government.”

This wasn’t just a veto—it was a populist cannon blast. Jackson cast himself as the defender of the working man, the farmer, the frontiersman, the forgotten citizen. In his mind, the Bank was an unelected engine of aristocratic influence, and he wasn’t going to let it calcify into something permanent.

The veto was controversial, even shocking to the establishment. But to Jackson’s base, it was electrifying. It drew the battle lines: Jackson and the people versus Biddle and the bankers. And in a way, it worked. Jackson won re-election in a landslide later that year.

The war wasn’t over. It was just beginning.

But vetoing the recharter wasn’t enough. Jackson wasn’t just trying to wound the monster—he intended to kill it. And that meant striking at its source of power: the federal deposits.

The Removal of the Deposits

Jackson had vetoed the recharter, but the Bank still lived. Its charter wouldn’t expire until 1836, and until then, it remained the official fiscal agent of the U.S. government—holding federal deposits, issuing loans, and wielding immense influence. To Jackson, that wasn’t just a loose end but a direct threat. So, in 1833, he pulled the pin.

He ordered the removal of all federal funds from the Second Bank of the United States.

This was no minor policy tweak. It was a seismic power play. The Bank’s influence stemmed from one core fact: it held the government’s money. Removing those funds would cripple its power, cut off its ability to make loans, and send a message to the American public that Jackson meant business. But there was one problem—he couldn’t do it legally on his own.

By law, only the Secretary of the Treasury could initiate the removal of deposits. Jackson’s own Treasury Secretary, Louis McLane, refused. So did the next one, William Duane. Both men saw the order as rash and potentially illegal. Jackson fired them. Finally, he found someone who would comply: Attorney General Roger Taney (yes, that Roger Taney—of Dred Scott infamy), who stepped in as interim Treasury Secretary and executed the plan.

Jackson began diverting incoming federal revenue into various state-chartered banks—his so-called “pet banks.” These banks were often selected for their political loyalty rather than their prudence. In doing this, Jackson bypassed Congress, defied institutional norms, and effectively gutted the Second Bank with the stroke of a pen.

Nicholas Biddle, stunned and enraged, struck back. He used what tools he had left—tightening credit, calling in loans, and trying to induce a financial panic to force Jackson’s hand. But Jackson didn’t blink. In fact, the chaos that followed only reinforced his case: that one institution should never be allowed to wield so much control over the nation's economy.

I want to zoom in on this. Consider the situation. The President wants to destroy the Bank. To counteract the President, the Head of the Bank starts a recession. It’s a real, serious philosophical question - should the leader of the Bank of the United States have the power to start a recession? It does seem to lend credence to President Jackson’s point that nobody should have that power.

It was a brutal standoff. Two men—each larger than life, each convinced he was saving the Republic—locked in a battle over what kind of country America would become.

And the public? They were caught in the crossfire.

The Panic of 1837

Jackson won the war—but peace didn’t follow.

After the veto, after the removal of the deposits, after the humiliation of Nicholas Biddle and the expiration of the Bank’s charter in 1836… Jackson rode off into retirement convinced he had saved the Republic. But within months of his departure, the economy collapsed. What followed was one of the most devastating financial crises in American history.

The Panic of 1837 wasn’t a single event—it was a slow-moving disaster that revealed the structural fragility underneath Jackson’s populist victory.

Here’s what happened:

When Jackson scattered federal deposits into pet banks across the country, those banks did what banks do when unsupervised and politically juiced—they went on a speculative lending binge. Easy credit flooded the system, especially into western land speculation. State banks printed money with little regard for specie backing, inflating a bubble built on paper promises.

To rein it in, Jackson issued the Specie Circular in 1836—an executive order requiring that public lands be purchased only with gold or silver. His aim was to curb speculation and restore monetary discipline. But in doing so, he inadvertently triggered a liquidity crisis. People scrambled to exchange paper for specie. Gold and silver flowed out of the country. Credit markets froze. And when the Bank of England raised interest rates in 1836, cutting off British capital to the U.S., the whole house of cards collapsed.

By the way - I profile the Panic of 1837 in my book - Timeless Wealth - when discussing how John Jacob Astor survived this period and even thrived. It’s worth a read.

Banks failed. Businesses shuttered. Unemployment surged. Cotton prices—the backbone of American exports—plummeted. States defaulted on their debts. The country plunged into a deep depression that would last for years.

And Jackson? He was gone. His successor, Martin Van Buren, took the fall—nicknamed “Martin Van Ruin” by political opponents as the economy crumbled around him.

Jackson had destroyed the monster. But with it, he may have also destroyed the only institution capable of managing the financial system with any semblance of control.

Legacy: A Nation Without a Rudder

Jackson won the war, but what followed wasn’t peace—it was drift. After dismantling the Second Bank, the United States entered a long period without any central financial authority. From 1836 until the creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913—nearly 80 years—the U.S. had no central bank. No lender of last resort. No coordinated monetary policy. And the results were, to put it mildly, mixed.

This period—often romanticized by critics of central banking—was anything but smooth. It was marked by a series of devastating panics: 1837, 1857, 1873, 1893, and 1907. Each one triggered waves of bank failures, economic depression, and political unrest. In the absence of a stabilizing institution, the American economy was like a tall ship in rough seas—buoyant at times but with no keel to keep it from capsizing when the winds turned.

This brings us to an important point—a critique often made by libertarian economists and writers like G. Edward Griffin, author of The Creature from Jekyll Island. Griffin argues that the economy and banking system, left to their own devices, will self-correct, that booms and busts are natural and that the market, like water, finds its own level if left unmanipulated.

There’s some truth in that. Markets do self-correct—eventually. But history shows us that “eventually” can mean years of human suffering: unemployment, starvation, lost savings, and ruined lives. In the wake of the Panic of 1837, self-correction took nearly a decade. During the Depression of the 1870s, it took longer.

The question, then, is not whether markets stabilize. It’s whether societies can afford the wait.

Jackson didn’t believe in central control. He believed in hard money, limited government, and the will of the people. But the absence of a central bank didn’t result in a healthy, balanced economy. It resulted in chaos—a boom-and-bust rollercoaster that ironically led to even more government intervention in the long run.

So, what is the legacy of Andrew Jackson’s war on the Bank?

It’s complicated. On one hand, he struck a powerful blow against entrenched financial interests and reminded the country that democracy means accountability. On the other hand, he left behind a financial system that was less stable, more prone to panic, and ultimately incapable of managing the demands of a growing industrial economy.

In killing the monster, Jackson may have created a new one—an economy untethered, vulnerable to the very forces he so desperately tried to protect it from.