The Central Banks - Part 3

The Revolutionary War has ended. The colonists successfully escaped Great Britain's yoke and now face an economic abyss.

The scale of the issues facing the new nation was dramatic. They were drowning in debt—the government owed $54 million ($1.12 billion in inflation-adjusted figures), and the states an additional $25. To compound matters, the Federal Government had no taxing authority and couldn’t even print money, yet states could, so there was no uniformity of currency across the nation.

Lastly, the government had no reliable revenue source, which meant it could not pay its employees. Consider, too, owing the equivalent of $1.12 billion with no reliable way to make money.

That was the predicament.

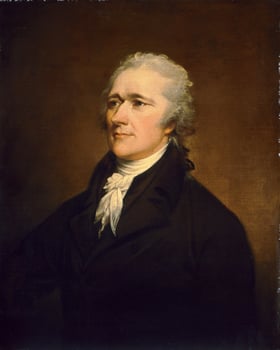

Into the breach steps the great Alexander Hamilton.

If we stopped there, this alone would be an inspiring story. But the story is only beginning. He arrived in America in 1772, just as tensions with Great Britain were heating up. Hamilton swiftly made a name for himself on the Patriot cause, writing fiery pro-independence essays. He became Washington’s aide-de-camp, serving as his right-hand man, and even led soldiers in combat during the Battle of Yorktown.

The man was relentlessly driven. And he was self-educated. While at King’s College (now Columbia), he taught himself economics, finance, and law. When the war broke out, and he entered the army, he was known to still carry a book with him. Or, if we harken back to the Federalist Papers - consider this. Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay wrote 81 papers. Hamilton accounted for fifty-one of them.

In addition to all of this, Hamilton was obsessed with order, discipline, and a strong government. Suffering alongside Washington at Valley Forge, witnessing first-hand the difficulties of having no money, Hamilton became convinced that the new nation’s problems were not only the British but themselves.

Something had to be done.

Hamilton’s Grand Plan: A National Bank to Save America

In December 1790, Hamilton submitted his report to Congress, meticulously laying out his plan. He took inspiration from the Bank of England and used it as a blueprint for what a national bank could look like in America.

His vision?

A powerful financial institution that could issue its own paper money would provide a secure place to hold government funds, facilitate commercial transactions, and, most importantly, serve as the federal government’s financial backbone—collecting taxes, managing debt, and ensuring the country’s finances didn’t collapse under its own weight.

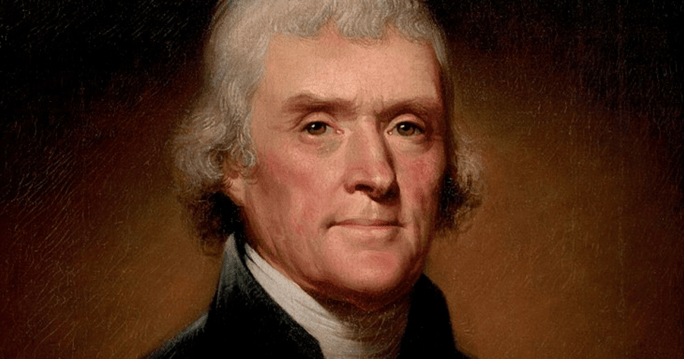

The plan immediately underwent hostile fire. That great American statesman, Thomas Jefferson, adamantly opposed the First Bank. His opposition deserves some expounding upon. Generally—I think—financial history right now is colored by who is the victor (like all history). The Federal Reserve system is currently not only the orthodoxy but also the winner. So I think my man TJ gets a short shrift on why he was so opposed.

Jefferson’s Opposition

Okay - so given the chaotic situation of the time, why be opposed at all?

Jefferson had multivariate and principled reasons for opposing the creation of a Central Bank.

The first was a matter of vision. Jefferson saw the United States as a nation of self-sufficient farmers, not one dominated by finance and industrial elites. He believed that true American prosperity lay in low debt, land ownership, and independence - not in complex banking systems run by East Coast financiers. In his view, a central bank wasn’t just an economic tool - it was a direct threat to the common man, a mechanism for moneyed elites to ensnare farmers in endless cycles of debt.

The second opposition was legal, and I think Jefferson was probably right. The Constitution does not explicitly authorize the federal government to create a national bank, and Jefferson saw this as a blatant overreach. Where would it stop if the government could simply invent powers whenever convenient?

But it’s his third opposition that’s most fascinating. Jefferson was a staunch believer in hard currency economics. To him, gold and silver were money. If you didn’t physically possess it, you didn’t have it. The idea of creating new money - issuing paper notes not backed by actual metal - was dangerous.

Jefferson feared that central banking would turn America into a debt-driven economy where farmers and small business owners would be permanently beholden to Eastern financial interests. Instead of landowners and merchants trading in tangible wealth, they would borrow against their future, trapped in an endless cycle of repayments, interest, and dependence.

On the other hand, Hamilton saw debt as a necessary tool for growth. To him, an organized, credit-based financial system was the only way to transform the U.S. into a real economic power. The two men weren’t just debating a bank - they were debating the future of the country itself.

The Aftermath: Hamilton’s Victory and the Bank’s Impact

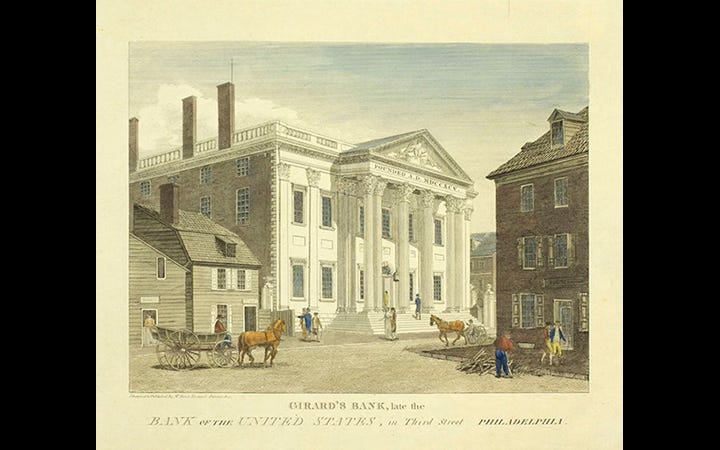

Hamilton ultimately won. The First Bank of the United States was chartered in 1791 with a 20-year term, headquartered in Philadelphia, and fully operational as America’s first central financial institution. It was a major victory for Hamilton’s vision—a structured, national economic system rather than a loose collection of state economies.

So what happened? Did the bank deliver on Hamilton’s promises? Or did Jefferson’s fears prove valid? The reality, as always, is more complex.

The Positives: What the First Bank of the United States Accomplished

-

Economic Stability - Before the bank, the country was drowning in debt and financial chaos. The bank created a centralized way to manage public funds, pay off war debts, and issue a stable national currency—all of which helped restore trust in the financial system.

-

A Stronger Federal Government - Hamilton believed that a strong national economy meant a strong national government. The bank made it possible for the government to borrow, lend, and regulate finance, giving the young nation more credibility—both domestically and internationally.

-

Encouraging Commerce & Industry - With the bank facilitating loans, businesses had more access to capital, helping spur trade, infrastructure projects, and early industrial development. This was especially beneficial for merchants and manufacturers, as Hamilton intended.

-

Boosted American Creditworthiness - Foreign nations saw the bank as a sign of financial responsibility. It allowed the U.S. to borrow at better rates, making it easier to raise funds for national projects.

The Negatives: The Costs & Consequences of a Central Bank

But not everyone saw the Bank as a success. While it stabilized the economy in many ways, it also came with unintended consequences—some of which fueled opposition for years to come.

-

Power Concentrated in the Wealthy Elite - As Jefferson predicted, the bank’s stock was largely controlled by private investors—many of them wealthy merchants and foreign investors. The financial system now favored bankers, creditors, and commercial interests over small farmers and laborers.

-

Didn’t Solve the Divide Between North & South - The bank heavily benefited Northern business interests (trade, finance, industry), but its impact on agrarian states in the South and West was minimal. Many Southerners still saw it as an engine of economic inequality.

-

Political Resentment & a Growing Divide - The bank became a symbol of Federalist power, fueling deep opposition from Jeffersonian Republicans who saw it as a tool for big government overreach. This financial war deepened the political divide in the early U.S. and set the stage for future conflicts over banking.

-

Expensive and Dependent on Government Favor—Unlike a purely free-market institution, the bank was propped up by federal authority, meaning it needed government approval to continue. This made its existence highly political, which, as history would show, was not a great long-term strategy.

It’s also important to ask—did the Central Bank create more problems than it solved? A true free-market capitalist would argue that the financial system would have eventually stabilized itself without government intervention. But there’s evidence that the massive increase in credit contributed to reckless speculation, particularly among early investors like William Duer, whose market manipulations triggered the Panic of 1792—the first major financial crisis in U.S. history.

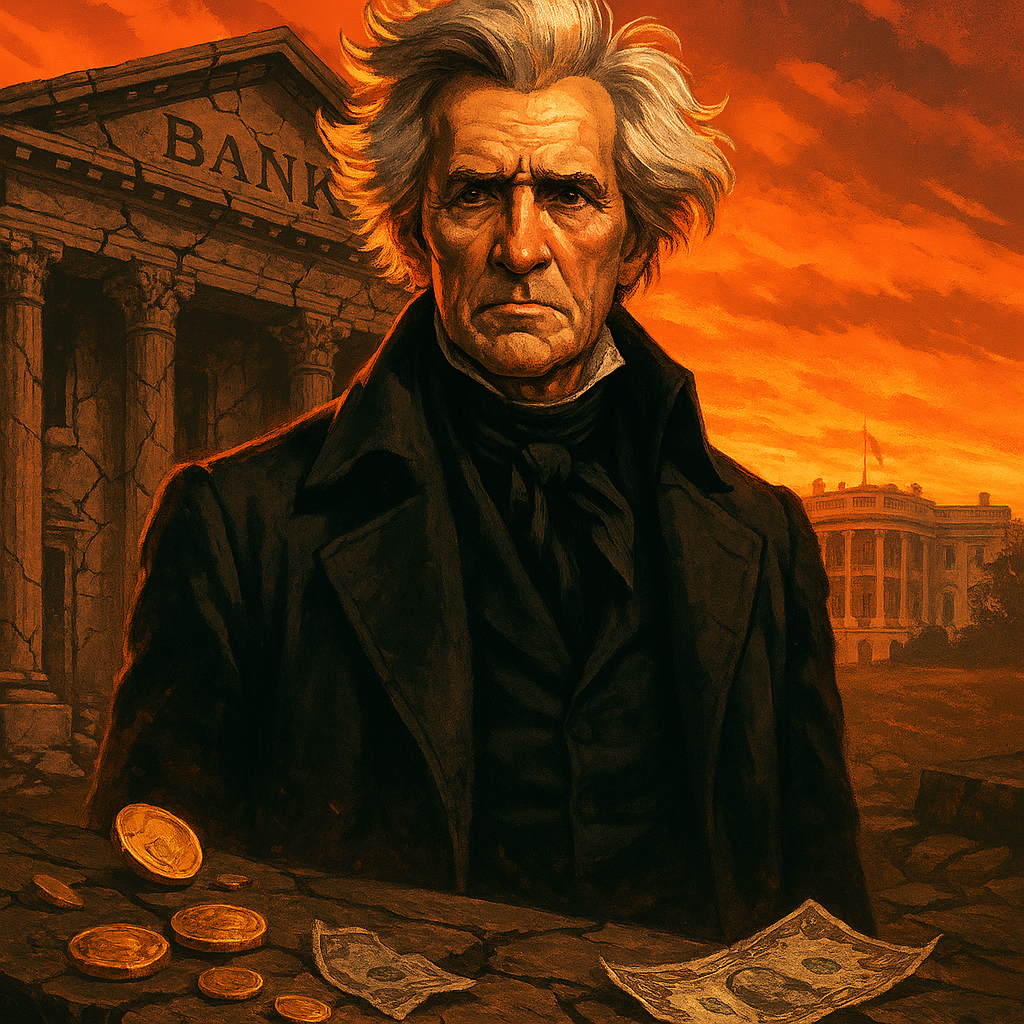

The Final Verdict: A Win for Hamilton, But Not a Permanent One

The First Bank of the United States did what Hamilton wanted—it stabilized the economy, strengthened federal power, and positioned the U.S. for long-term financial growth. But it also deepened political divisions, heightened fears of elite control, and never won full national support.

And ultimately? Jefferson’s side got the last laugh—at least temporarily.

When the bank’s 20-year charter expired in 1811, Congress refused to renew it. Jefferson’s camp had won—for now. However, as history would show, financial crises have a way of forcing governments to act, and just five years later, a new bank would rise to take its place.

The cycle would continue, again and again—right up to today's Federal Reserve.

And that’s exactly what we’ll cover in Part 4: The Rise & Fall of the Second Bank of the United States.

If you’ve enjoyed this deep dive into America’s first central banking experiment, you’ll love my book, Timeless Wealth. It explores how real estate has been the foundation of wealth-building for centuries—from the land-owning elites of early America to today’s smartest investors.

Understanding history is the key to understanding money and how to build and protect wealth in any economic climate.

📖 Get your copy here: Timeless Wealth