The Central Banks - Part 2

Last week, we explored the Massachusetts Land Bank, which was “sort of” an experiment in central banking. It was a constant fight between capital and labor, exemplified by wealthy merchants controlling all the actual gold and silver while farmers struggled to finance and build their own businesses.

But the first true attempt at Central Banking in the United States was …

Thanks for reading The Timeless Investor! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Let’s lay the groundwork here. The year is 1781. The American colonies are locked in a desperate struggle against a vastly more powerful Great Britain. You probably know about that war - the Revolutionary War. I assume …

The colonists had two major advantages. They had a home turf advantage (the ultimate home turf advantage) and quite a distance from Great Britain.

But they have one major disadvantage: they are totally broke.

Wars are needy—they require a lot of money. The banal logistics behind wars are where wars are actually won.

I remember being at Marine Corps Officer Candidate School, and the intimidating man, a veteran of my Major (multiple wars), was walking through each of us candidates and what we, the room, wanted to do after graduating. When questioned, everybody sounded off with “Infantry!” or “Intelligence!”, like good Marines.

One guy proudly shouted, “Supply!”.

The major looked at him with his sharp, battle-hardened eyes and said, “Son. That’s the most important job in the Marines. Good on you.” Then I felt sort of silly for being in the “infantry and intelligence” camp.

It turns out that real intelligence lies in the supply function.

But behind supply, there’s a need for money.

Lots of it.

The Founding of the Bank of North America

By 1781, the war had been dragging on for six long years. The American colonies had plenty of courage but no cash. Congress had been printing Continental Dollars, but they were essentially worthless by this point - hyperinflation had set in, and nobody trusted them.

There are a few reasons why this happened. First, the Continental Congress had no taxing authority, which is wild. But after all, we broke from Great Britain because we disliked taxes, so it sort of makes sense (although not really) that we assumed our government would then not be able to tax us.

Thus, the only way for the colonists to finance the war was to print true fiat currency as the Continental Dollar. Here’s the problem - dollars, printed en masse, backed by no hard currency (gold or silver) and no taxing capability?

You can imagine the issue.

It turns out that “not worth a Continental” was more than just an insult - it was an economic reality.

The colonies were running on financial fumes.

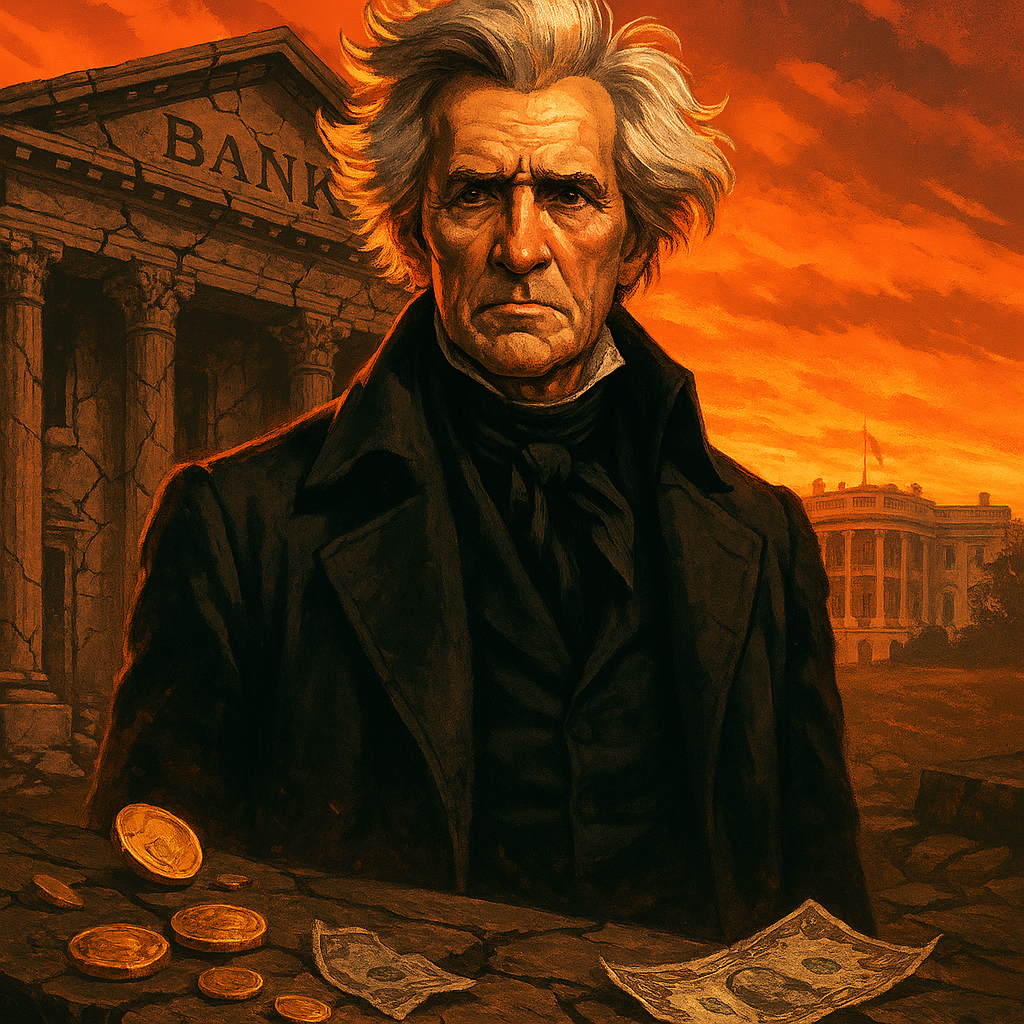

Without a real solution, the Revolution itself was at risk. Enter Robert Morris - the man with the plan.

A wealthy merchant from Philadelphia, Morris wasn’t just some paper-pushing bureaucrat - he was one of the few people in the colonies who actually understood finance.

Congress was desperate, and Morris had a plan:

Create a national bank to stabilize the economy, finance the war, and bring some order to the financial chaos.

And so in 1781, with Congress’s approval, he founded the Bank of North America -America’s first true attempt at a central bank.

Fun historical note - why the Bank of North America?

At this time, it was hotly anticipated that Canada would be part of the new United States, and thus, they wanted to create a nice, inclusive title to include the soon-to-be-added conquests north of the border.

Alas for our ancestors - it didn’t come to pass. And today, we get to share the longest unmilitarized border in the world with our Canuck brethren.

How the Bank of North America Worked

Robert Morris understood something critical: money needs backing. Paper money was worthless unless people believed it had real value. That had been the problem with the Continental Dollar—Congress printed massive amounts of it, but with no gold or silver reserves behind it, inflation had destroyed any trust in the currency.

Morris wasn’t about to make the same mistake. The Bank of North America issued notes backed by gold and silver, instantly making them more credible than the collapsing Continental Dollars. It functioned like a modern bank in several key ways:

-

It issued banknotes that could be used in transactions, restoring confidence in paper money.

-

It accepted deposits and made loans, providing a much-needed economic financial engine.

-

It acted as the government’s banker, helping fund the war effort and manage public finances.

The United States had something resembling a real financial system for the first time.

Did It Work?

For a while, yes.

The bank immediately stabilized the economy by providing people with a trustworthy currency.

It provided a way to finance the final stretch of the war, ensuring soldiers, suppliers, and contractors got paid. Most importantly, it laid the foundation for future national banks, proving that a centralized financial institution could help manage economic chaos.

But it also created fierce opposition.

The Backlash: America’s First Anti-Central Bank Movement

Not everyone liked the idea of a powerful, centralized financial institution.

-

State governments resented the idea of a federal financial entity controlling credit and money supply.

-

Wealthy merchants and elites worried about inflation and losing their grip on financial power.

-

The general public distrusted banks - the entire idea of centralized banking was still new, and memories of paper money failures were fresh.

The backlash was strong enough that in 1785, Pennsylvania revoked the bank’s charter, stripping it of its special status. While it continued operating as a private bank, it was no longer a national financial institution.

The Legacy of the Bank of North America

The experiment didn’t last, but it proved a point—a national bank could work. It showed that managing money was just as important as winning battles, and it set the stage for every future fight over central banking in the U.S.

Robert Morris’s vision didn’t die with the Bank of North America. A decade later, Alexander Hamilton took the idea further, creating the First Bank of the United States in 1791—the first real national bank under the new Constitution.

And that? That’s the battle we’ll cover in Part 3 next week.

👉 “If you enjoy deep dives into financial history, check out my book, Timeless Wealth - where I explore how real estate has been the foundation of wealth-building for centuries. Get your copy here: Timeless Wealth: Real Estate Through the Ages.