The Central Banks - Part 1

Partly as an exercise in self-education, I’m launching an educational series on the founding of the Central Bank, publishing every Wednesday. This series will trace the various iterations of the U.S. Central Bank before pivoting into the rise (and fall) of other central banking experiments throughout history.

Once this series concludes, we’ll expand into broader finance, economics, and real estate topics.

The topic of central banks is particularly important because like it or not, our modern economy is deeply dependent on these institutions. We live in an era where centralized economic management is considered optimal, despite ample evidence that intervention in the “invisible hand of the market” often leads to unintended consequences.

In other words: the track record isn’t great.

I draw this conclusion for two key reasons:

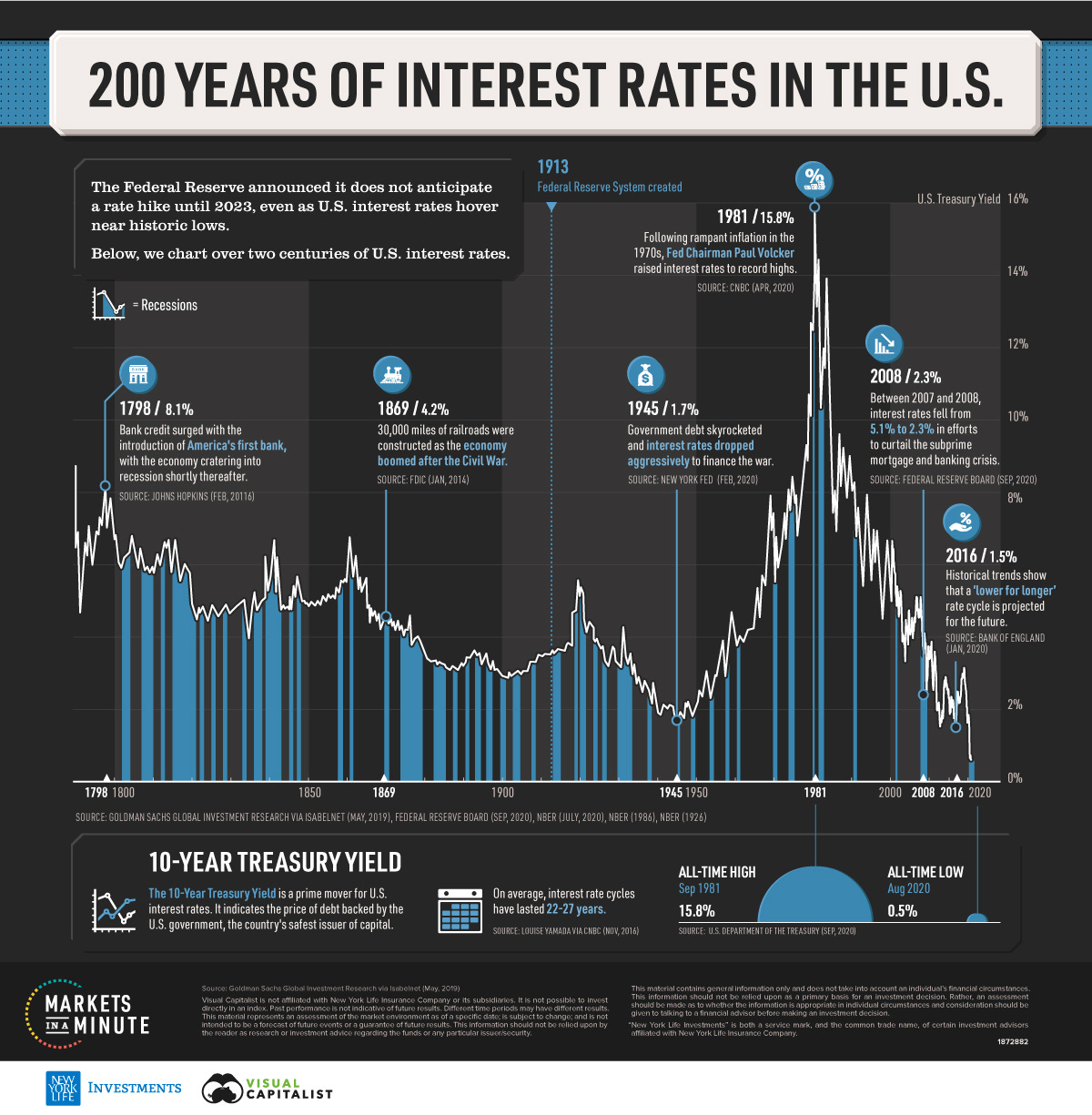

1️⃣ Financial crises are less frequent post-1913 but far more severe.

- Central banks may have reduced volatility, but when things do go wrong, they go really wrong.

2️⃣ Inflation has significantly increased under the Federal Reserve.

- Historical inflation estimates are difficult to verify, but some sources estimate that pre-Fed inflation was 0.4% annually, compared to ~3.5% post-Fed.

- This monetary system has benefited asset owners (real estate, stocks) at wage-earners' expense, contributing to wealth inequality and economic instability.

I’m not a gold bug, so I’m not advocating a return to a pure hard currency standard (well… not 100% anyway). But our inflationary system has undeniably made life much harder for working Americans and made real estate and other hard assets unaffordable for many.

This housing affordability crisis is one of the greatest threats to the stability of our democracy.

That’s why we should all understand these stories—monetary policy is too important to leave solely to economists and bureaucrats.

So let’s begin our Central Bank series with the first American central banking experiment—the Massachusetts Land Bank of the early 1700s.

The Tale of the Massachusetts Land Bank (1740)

To begin our tale, we must understand one thing: everything in the early 1700s depended on precious metal currencies, and the American colonies were desperately short of them.

This makes sense when you consider the colonists' situation. They weren’t an economic powerhouse. The mothership—Great Britain—controlled the real wealth, hoarding gold and silver reserves while sending only a trickle of hard currency to the colonies. As a result, only the wealthiest elites had access to real money, while the average farmer or tradesman was stuck bartering or relying on IOUs.

That brings us to Massachusetts, a colony that experienced an even worse financial crisis than usual after one of the most disastrous military failures in British history.

1711: The Failed Invasion of Quebec & The Massachusetts Cash Crisis

In 1711, the British launched an invasion of Quebec, the capital of New France. This was a major power play in Queen Anne’s War, and Massachusetts played a central role in financing the operation.

It didn’t go well.

In fact, it ended in one of the worst Royal Navy disasters of all time. A massive fleet carrying 7,500 troops set sail from Boston, bound for Quebec. But thanks to bad maps, worse navigation, and even worse luck, several ships wrecked off the coast of the Saint Lawrence River. Nearly 1,000 men drowned before they even reached the battlefield.

The invasion was abandoned. And Massachusetts? It was left holding the bag.

Since Boston had been the economic and logistical hub of the operation, the failed invasion wrecked the colony’s finances in several key ways:

1️⃣ Massachusetts had financed the war largely on its own.

- Unlike Britain, the colony had no international lenders to borrow from.

- The plan was to recoup the investment from spoils of war—which, of course, never materialized.

2️⃣ To cover the war costs, Massachusetts issued paper currency.

- This wasn’t backed by gold or silver because there wasn’t enough of it.

- More paper money = inflation, making life harder for ordinary people.

3️⃣ The disaster angered Britain, which cracked down on colonial financial independence.

- The British government was frustrated with Massachusetts’ growing financial autonomy.

- Britain tightened economic controls to prevent colonies from issuing more paper money, cutting off one of the only ways the colony could stabilize its economy.

This set the stage for a major economic experiment in Massachusetts that infuriated the British government and the wealthy merchant class.

By 1740, Massachusetts was broke. Again.

Gold and silver? Scarce as ever. Britain’s policies? Strangling the economy. Trade? Sluggish. The colony needed a financial workaround and fast.

So, a group of farmers, small business owners, and tradesmen decided to sidestep the hard money problem entirely. Why not back money with something else if there wasn’t enough gold or silver?

Enter: The Massachusetts Land Bank.

How It Worked

The idea was simple:

- Instead of backing money with gold or silver, the Land Bank issued paper notes backed by land.

- Landowners mortgaged their property in exchange for these notes, which circulated as cash to keep the economy moving.

- Farmers and tradesmen loved it. They could finally access credit without relying on rich merchants hoarding hard currency.

It was an early experiment in financial democratization, a direct challenge to the economic power structure of the time.

But some people really hated the concept. Those people included the Crown, which was already wary of the colonies' growing independence from the mother country, and the wealthy merchant class, which had previously controlled the means of lending and currency. The Crown, in particular, worried that if the colonies could produce their own currency independently, then it would ben't be a long step from there to demand full political independence.

As such, we will never fully understand the impact of the Land Bank because the Crown shut it down way too quickly. In 1741, the Crown extended The Bubble Act to the colonies, thereby shutting down the Massachusetts Land Bank. The result was disastrous for the common man—many people were utterly ruined.

We do know that previous attempts to launch paper currency in the colonies (Massachusetts again in the late 1600s) had resulted in rampant inflation, and this, more than anything, was what the wealthy merchant class feared.

The first battle over central banking in America ended the way many others would—with the financial elite winning and the common man left in ruin.

Thus ends the first in our article series on The Central Banks.

If you enjoy deep dives into historical financial experiments like this, you’ll love my book, Timeless Wealth. It explores how wealth has been built and preserved through real estate for centuries—revealing the strategies that have stood the test of time. Get your copy here.